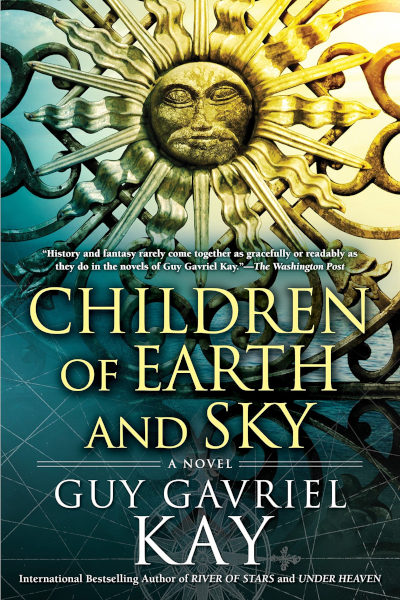

"Children of Earth and Sky" by Guy Gavriel Kay

I should have known Guy Gavriel Kay wouldn’t let me down. Kay’s books are often classified as fantasy, but I think they’re firmly historical fiction. I don’t have anything against fantasy—I grew up on J.K. Rowling and Philip Pullman, and I still love it—I just don’t think Kay’s books fit the description. Kay’s characters believe in mysticism, but I think that’s more a reflection of how people used to see the world than an effort to inject magic into the proceedings. Sword-and-sorcery novels these are not.

Kay also doesn’t set his novels in real historical settings. He twists the world enough to give him freedom to alter the story but not so much that the setting becomes unrecognizable. Children of Earth and Sky is set in a version of Europe in the second half of the 15th century; primarily in what would have been Venice, Dubrovnik, and Istanbul.

The story follows a number of characters, but the focus is on five: a daring female pirate, an artist conscripted into espionage, a disgraced noblewoman desperately trying to control her fate, the younger son of a wealthy merchant, and a boy captured by the forces invading Christian Europe (our Ottomans) and trained as an elite soldier (our Janissaries). Kay is a master of interweaving their stories. The characterization is exquisite. The plotting is clever, and the world is incredibly detailed. And, as is always the case with Kay, the writing is beautiful.

Stories do change. We do not understand the world. We are not made that way.

My only complaint with the book is the pacing. Somewhere between half and three quarters of the way through, it began to drag. Kay’s novel’s aren’t thrillers, and they’re not action-packed. I’ve read several of his other books, and they’re often told at a speed I relish. But the pacing bothered me more in Children of Earth and Sky because it seemed off; it was slow unnecessarily and in ways that didn’t contribute to plot or characterization.

But Kay brought it back. The final chapters were riveting, and I had to finish the book in one long last push. One aspect of the ending that keeps me thinking, though, is that all of our point-of-view characters have happy endings. Kay doesn’t shy away from realistic portrayals of a time and place that were harsh and violent and unforgiving; indeed, many of his rich observations arise from those aspects of the setting. I’m more sentimental than most, and the ending of the novel was the best part. But it still left me, for the first time, doubting the vivid world Kay creates for us.